9 – Bess the Lucky

Over 10,000 horses went to the First World War from New Zealand, and Bess our Hero Horse number 9 was among them. She was one of only four to return home and came to symbolise the service and sacrifice that brave soldiers and their steeds gave to secure the freedom we all enjoy today. She has been nominated by John Bickley, our New Zealand Ambassador.

Our New Zealand Ambassador, John Bickley.

This is her story… Each volunteer mounted rifleman was supposed to bring a horse, and they were bought by the New Zealand government and issued back to the soldier if the horse was deemed suitable. The horses had to be aged 4–7, 14–15.2 hands in height, strong and not too light a colour. Stallions were not allowed and geldings were preferred. ‘NZ’ was branded on one hoof, the identification number on another hoof. In addition, more than 1,000 horses were donated to the government.

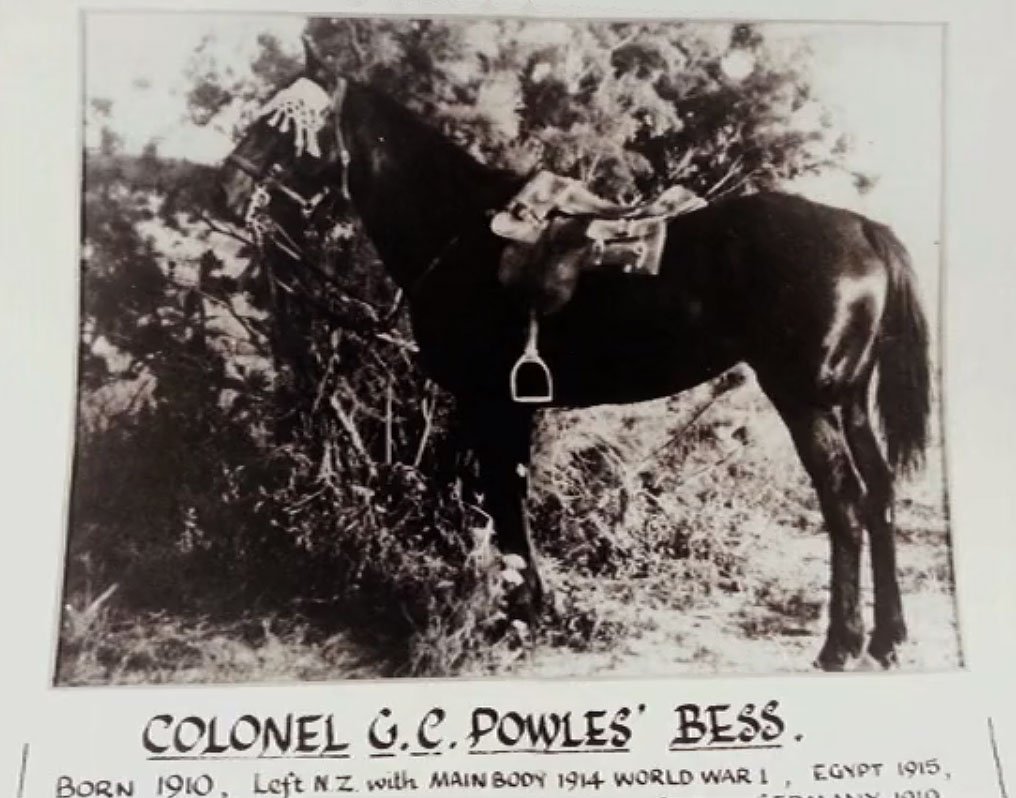

One of these ‘gift’ horses was a four-year-old black thoroughbred. Bred by A. D. McMaster of Matawhero, near Martinborough, in 1910, she was by Sarazen out of Miss Jury. She was known as F. A. Deller's ‘Zelma’ prior to being presented to the New Zealand Army. ‘Zelma’ was allocated to the Wellington Mounted Rifles Regiment and selected by Captain Charles Guy Powles, who renamed her Bess.

Powles had previously served in the South African War. An officer in New Zealand’s Staff Corps at the outbreak of the First World War, he became brigade major to the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (NZMR).

He served with the NZMR in multiple campaigns during the war, becoming commanding officer of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles and ending the war as a lieutenant colonel. He wrote two books on the NZMR, including: The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine with Major A. Wilkie (1922) and History of the Canterbury Mounted Rifles 1914–1919 (1928).

Bess and Powles left New Zealand with the main body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in October 1914, bound for Egypt along with 3,815 horses, who were transported in rows of cramped stalls, some exposed to the weather. The men had to groom them, rub their legs to prevent swelling, and exercise them daily on coconut matting on the deck. Over a hundred died while being transported and their bodies were thrown overboard.

Nearly all of the 10,000 horses went initially to Egypt. More than half were riding horses, like Bess, used by the troops and officers. Nearly 4,000 were draught horses or packhorses used for artillery and transport purposes. Many of these ended up on the Western Front. Very few horses were used at Gallipoli, so most, including Bess, remained in Egypt during 1915. From late 1915 the horses were reunited with their men as they returned from Gallipoli.

Bess remained in the Middle East along with several thousand other New Zealand horses. They were assigned to the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade which, as part of the ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) Mounted Division with Australian Light Horse brigades and Royal Horse Artillery batteries, served in the Sinai Campaign of 1916 and the Palestine campaign of 1917–18.

Riding horses were used throughout by the mounted troops. The men were not cavalry, fighting from their horses. Rather, the horses allowed the riflemen to move rapidly to new positions. The men operated in groups of four and, when they dismounted to take part in actions like infantry, one man would be left behind to look after the horses.

The conditions on the ground in both the Sinai and Palestine were physically trying for the horses. They carried heavy loads – a fully loaded horse carried about 130 kilograms – including rider, weapons, two bandoliers of ammunition, forage, blankets, food and water. They had to travel long distances on difficult terrain, putting up with ticks, fleas and biting flies, shortages of food and water, and challenging weather – from extreme heat, burning sand and blinding dust, to cold nights and driving rain.

Inevitably horses lost condition. Some died, others were too weak to continue and were evacuated to hospital. In 1917, immediately before the Battle at Ayun Kara, some horses went without water for up to 72 hours. Horses also died as a result of wounds from enemy artillery fire or aerial attacks. The men became emotionally and physically dependent on their horses – and often used their shadows to get protection from the midday sun.Conditions were no better for horses on the Western Front. Food, water or suitable shelter were in short supply, and during winter they suffered because of the wetness and mud. Sometimes horses were killed or wounded by shell fire or aerial bombing in rear areas where they were tethered or stabled together.

It is unclear exactly how many New Zealand horses survived to the end of the war. Records suggest some ‘original’ horses were still with their units. Bess was one such horse. Shortly before the Palestine campaign ended Powles and Bess joined the New Zealand Division in France. After France, she served with Powles during the occupation of Germany’s Rhineland. At the end of the war an acute shortage of transport, and quarantine restrictions related to animal diseases prevalent overseas, prevented most horses from returning to New Zealand.

Horses serving in Egypt were pooled with other British army horses. The fittest were initially kept but most were not. Those fit for work were sold locally, while those deemed unfit were killed. Some men tried to have their horses deemed unfit, rather than have them sold locally, concerned that the locals would mistreat them. A few of the horses on the Western Front were eventually repatriated to England.

Bess was one of just four horses originally from New Zealand that were subsequently transported home. All had belonged to officers associated with General Sir Alexander Russell: Beautiful to the late Captain Richard Riddiford, Dolly to General Sir Alexander Russell, Nigger to the late Lieutenant Colonel George King and Bess to Powles.

The horses were repatriated to England in March 1919 and subjected to 12 months quarantine. Bess apparently took part in a victory parade in Britain. The horses arrived back in New Zealand in July 1920.

After the war Bess was the model for the sculpture of a wounded New Zealand horse on a memorial to the Anzac mounted troops at Port Said in Egypt. That statue was destroyed in the 1956 Suez crisis, and copies were made and erected at Albany in Western Australia and in Canberra. Bess continued to serve Powles on her return to New Zealand in 1920 while he was a commander at Trentham and later as headmaster at Flock House, an agricultural training school for dependants of war veterans.

Bess produced several foals, and died on land close to Flock House in 1934. Powles buried her at Flock House and erected a memorial. The square-shaped memorial, topped by a large rock, features two memorial plaques. One denotes the places where Bess served during and after the war. The other bears an Arabic inscription that translates as ‘In the Name of the Most High God’.

John tells us…I joined the New Zealand Army at 16 via a cadet group and served with 1 & 2/1 Battalions of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment. Today I honour all troops and animals from all wars by riding in remembrance.

I especially remember the Mounted Riflemen and their Steads from Australia and New Zealand and Britain including my Grandfather and his Brother at this time 100 years ago capturing Beesheeba and successfully turning the tide of war and ending German control of the region and indeed the long ruling Ottoman Empire. I display my Grandfathers Hat Badge and Medals proudly… John Michael Bickley 10 Nelson Squadron of Canterbury Mounted Rifles New Zealand Mounted Rifles.